It was International Day of Happiness the other week (20th March). Always a strange occasion for me – should I use the opportunity to share my happiness expertise with the world or get out in the actual world and make sure that I, at least, have a happy day?

Well, this year International Day of Happiness fell on a Saturday, plus it was a sunny day in Scotland. And so it had to be a few choice tweets and then off I went to the local hills. It turned into a 10 out of 10 happy day over here.

Last week also saw the launch of the World Happiness Report – every year since 2012 the report gets released on International Day of Happiness. This year, 2021, the report was dedicated, unsurprisingly, to the effects of COVID. In years gone past I’ve not had the time to read the report in full – it’s more than 200 pages long! Not exactly happy reading, but certainly a purposeful use of time for my currently unemployed self.

So what does the latest World Happiness Report tell us about happiness since COVID times began?

Happiness has barely budged as a result of COVID – a case of human resilience, a poor measure of happiness, or hidden inequalities?

The overall conclusion of the report is that there has been little change in world happiness. Overall “happiness rankings” have remained more or less the same as previous years, with Finland maintaining its crown as “the happiest place in the world” and the usual suspects – the Nordic countries, a few of the small wealthy European countries, New Zealand – following suit in the top 10.

Surprised? I sort of am, but really I am not. There are several reasons that happiness appears to have not changed and much that we can learn by looking more deeply at the numbers and beyond – some acknowledged in the report, some not.

1. Human Resilience

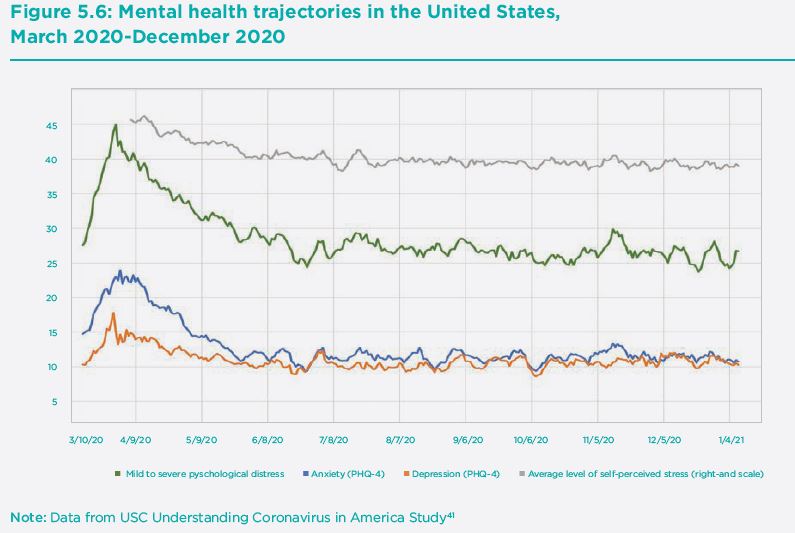

The first is to recognise and celebrate human resilience. Human beings are generally highly adaptive. Situations that we may imagine to be terrible either aren’t as terrible as we thought they would be when they eventually happen, and then, after they have happened, we quickly find ways to adapt. Whilst there has no doubt been severe struggle, most of the deterioration in happiness and mental health took place early on (March 2020 to May 2020) and then largely recovered later in the year (on average, see later on hidden inequalities). The graph on mental health data from the USA illustrates this well, as do my own happiness levels which I tracked all year long and you can read about here.

Many have found other ways to cope – through connecting more deeply with friends and family, for example. Many of us have been stuck with the same beings for most of the year. Though that can be difficult, our relationships can be one of the most powerful sources of happiness. There is also our capacity to emotionally regulate, that is adapt our emotions to suit the context we are in.

And let’s be honest, the typical way of living isn’t particularly fulfilling – busy, stressed, and lonely. This pandemic has given us breathing space to re-evaluate what is important to us.

2. A poor measure of happiness

A second important aspect to consider is what constitutes happiness. The main measure of happiness in the World Happiness Report is, in my opinion, not much of a measure of happiness.

The celebrated “happiness league tables” that are published in the World Happiness Report each year are based on a question that is unlikely to sound much like happiness to most people.

They ask people to “think of a ladder, with the best possible life for them being a 10, and the worst possible life being a 0.” People are then asked to “rate their own current lives on that 0 to 10 scale.”

It’s a funny old question. It has it’s uses and it is worth asking yourself from time-to-time, but it is a bit concerning that it forms the cornerstone measure for a happiness report. There are two well-known issues with this type of question and the World Happiness Report does little to address them.

First, people’s answers are based on whether they have achieved specific culturally conditioned life goals, and not whether they feel happy in their day to day life. It would be a misnomer to think that in Finland – the top ranked happy country – people sit around laughing and smiling a lot. In fact, based on the latest publicly accessible data they rank 41st with regard to how much they laugh and smile.

Second, people’s answers often depend on relative comparisons rather than absolute ones. A person will answer well based on how they have done compared to others. COVID may have messed up a lot of people’s lives, yet we may still answer this question high if relative to others we didn’t do so bad. We may count ourselves fortunate compared to the stories we’ve heard about what has happened to others – death, isolation, unemployment. . .

That being said, there is some analysis of other questions related to happiness in the World Happiness Report. Laughing and smiling, for instance, and also negative emotions such as worry, sadness and anger. Yet, again, the amount at which people laugh and smile has barely budged on average. Only negative emotions seem to have on average gotten worse, though not by that much.

3. Hidden inequalities

However, the top-line conclusion that happiness hasn’t changed that much overall masks what has been happening in different corners of society across the world. Some countries or groups of people within those countries have experienced large happiness declines on average, whilst others have in fact improved. And we may base our predictions as to what happened to others on what happened to us. If we have had a rough/spectacular time, we may be oblivious to what has been going on for others elsewhere. The differences in what happened to us and others may surprise us, but it is important we try to understand them and the World Happiness Report unpicks many of these.

- Country differences

Here in the UK, for example, the declines in happiness have been quite large. On the ladder question average levels were 6.8 in 2020 compared to 7.2 over the previous three years (a 0.4 fall) with only 12 countries of the 95 countries surveyed dropping by a larger amount (the largest of all surveyed European countries). Some countries, including Croatia (+1.0), China (+0.6), and Greece (+0.3), experienced substantial increases.

What we have to acknowledge is that some countries have managed this pandemic very well. And whilst it has felt like a permanent lockdown in the UK, in other parts of the world where governments acted quickly and decisively lockdowns were not so severe. Early restrictive measures received public acceptance and were acted upon by citizens (owing to higher trust and less individualistic mind-sets, which I’ll come onto in a bit below), resulting in the virus being quickly contained, with minimal deaths and little economic disruption.

Life has largely returned to normal in many parts of the world through the adoption of non-pharmaceutical interventions. And although this was clear very early on in the pandemic, many of the early worst performing COVID countries set about opening up their economies quickly, only to then experience further infection waves that they have struggled to contain.

2. Within country differences

That being said, the USA, which has had the highest absolute death toll and one of the higher death rates per 100,000, did not experience an overall drop in their life evaluation. Yet, this hides inequalities within the country, as is a case with most countries. Some may have suffered immensely, but if others have done OK, or even quite well, then this can on average balance the numbers out overall.

We know from data across the world that particular groups have suffered more than others. For example, many women have fared worse overall, owing to increased time pressures at home due to imbalanced childcare and home-schooling. Plus, women tend to have experienced disproportionate losses owing to working in industries that have been the most vulnerable economically in the pandemic, such as retail and hospitality. However, it is also evident that men that became unemployed during the pandemic have suffered psychologically much more than women that became unemployed (a common finding outside of pandemic).

There are also differences between the young and old, with older people reporting higher life evaluations this year compared to last. Younger people have suffered and continue to suffer with restrictive measures that are largely there to support the health of older people more vulnerable to the infection.

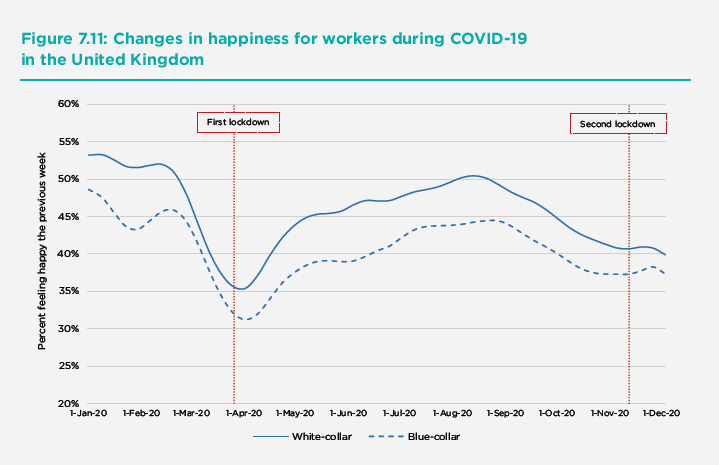

Even those in work have suffered with those in blue-collar/manual jobs doing worse than those in white-collar/non-manual jobs. See graph below.

There have also been factors that are protective that some have access to and others don’t. For example, being active outside daily, staying connected, and having a positive psychological mind-set all helped, whilst pre-existing mental health issues, poor social support, and financial insecurity do not.

The bottom line here is that this pandemic has not affected everyone equally.

‘We are all sailing in the same storm, but we are all on different boats’.

Importance of social trust

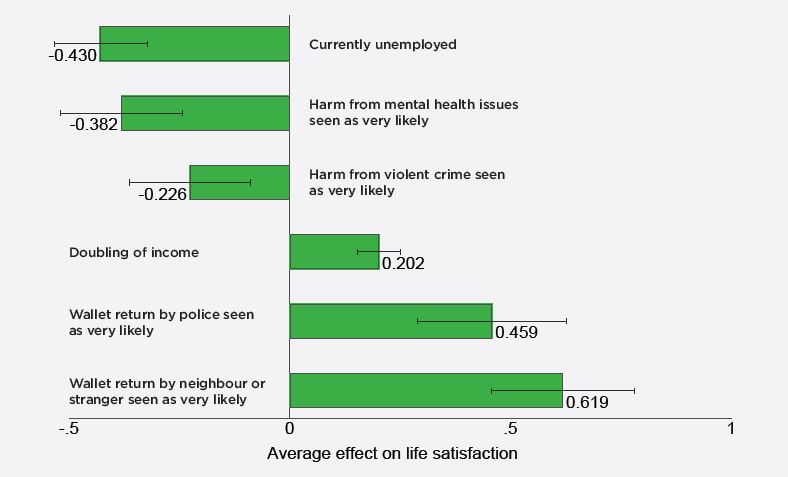

One things that resounds throughout this year’s World Happiness Report is the importance of social trust. We’ve long known its importance in happiness and to begin with this year’s report illustrates how trusting that someone in the community would return a wallet if found is more important for how people evaluate their lives than nearly any other factor (see figure below).

However, the role of trust – both neighbourly trust and trust in government – in the pandemic has been immense. For example, trust has been associated with lower death counts, and it is likely that this is owing to generally more consideration for others in the community and greater likelihood to trust interventions and pronouncements from public officials.

Countries that are less community minded have done much worse, being less likely to engage with non-pharmaceuticals interventions, owing to distrust, individualism, & susceptibility to false information, resulting in a successive waves of covid infections that were as bad as the first.

Dystopia

One of the most striking things in the World Happiness Report is how much happiness there is the world that can’t be explained. The Report concentrates on what can be explained, not what can’t be explained. That’s great. Yet, of Finland’s 7.8 out of 10 score on the happiness-ladder question, at least 3 of those points cannot be explained by any known factor.

Whilst this is no surprise when trying to establish the relationship between two factors, sometimes very poorly measured and inadequately defined, it does illustrate that there is still so much that is not known about happiness from a scientific perspective. For me this illustrates a problem with boiling happiness down to numbers. Numbers, of course, have their place in a debate, but they also have their limits and there are other ways to consider the world.

The focus on numbers comes because the Report is largely led by economists, and white male ones at that. Though the Report has diversified since its inception, its perspective remains limited and room is needed for further perspectives on happiness. Happiness must, of course, go beyond numbers.

Policy

Nevertheless, this year’s World Happiness Report gives us a lot to think about when it comes to how to set about supporting people’s happiness as we move forwards. What is abundantly clear is that there have been diverse effects on people’s happiness this last year. It would be fair to conclude that much of this was the direct result of the pandemic and the accompanying government responses. How things are dealt with from here will be just as crucial, if not more so.

Whilst there is considerable published evidence (overviewed in Chapter 6 of the Report) about what has helped people cope, it will be years before this evidence finds its way into actual policy that could improve people’s lives. In fact, by the time evidence is considered reliable enough to inform policy, we will (hopefully) be long through this. That’s how the policy process works – taking several years to get irrefutable causal evidence. But that is a shame, because in the meantime policy that does little to protect and promote happiness and broader wellbeing will persist.

As the World Happiness Report illustrates each year there are clear differences in happiness across countries throughout the world. It would be crazy to boil this down to individual choice – to think that a person’s given level of happiness has arisen simply as a result of their own choices – as is too often purveyed in individualistic societies. Of course, there are systemic reasons as to why happiness differs both between and within countries and that a person’s environment, as well as the policy that public officials enact on citizens to create or support that environment, influence our choices to be happy. We have long known this. Collective wellbeing is more than the sum total of the happiness of each individual.

Build Back Better

The pandemic illustrates that some will suffer more than others, not from choice, but just by happening to live in a certain place, working in a certain industry, and of a certain age, gender, race, among other things. The cost of this pandemic has been immense and whilst many have lost far more than others through no fault of their own, we need to find our way through together.

As has been said a lot this past year we need to Build Back Better. We have long known that much about our modern societies is not supportive toward human and planetary wellbeing and moving forward needs greater care and compassion for others and the environment that support. And this leaves me to relay one of my favourite findings relating to the pandemic this year – public health outcomes have been far better under female led governments. Curious, don’t you think?

********************

I love feedback – please feel free to comment or share this post

And here are some other post I’ve written related to happiness and policy that you might like

Happiness may be a choice – except that it’s constrained by vested economic interests

Maybe enough people got pumped with anti-depressants in 2020 to skew the figures, since I heard that depression and suicides rose last year as a result of Covid.

Hi Brian, that might be a possible explanation. There is evidence that there has been some increase in antidepressant use in England (mostly at the start of the pandemic – March 2020), and that does conform to the rise in mental difficulty illustrated in the graph of mental health trajectories (see this – https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40199-021-00390-z). On suicide, there is little evidence that rates have risen at this point (see this https://www.bmj.com/content/371/bmj.m4352) – it might take a while before more is understood on these issues.